from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

Martin Creed Plays Chicago

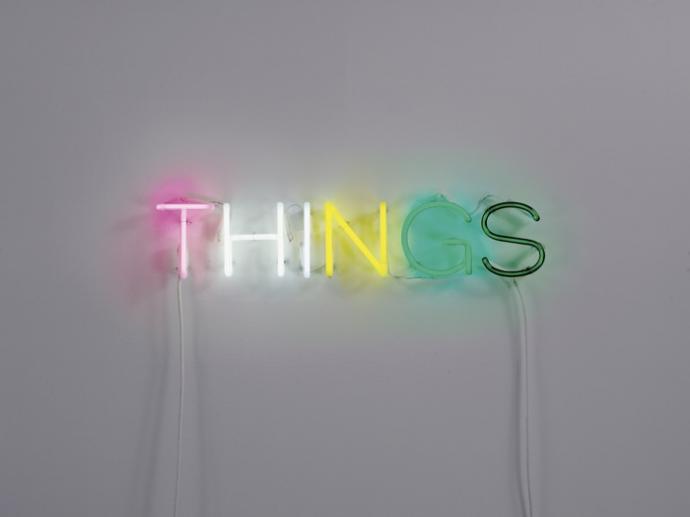

August marks the eighth month of Martin Creed’s yearlong cumulative exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Martin Creed Plays Chicago opened in January 2012 with Work No. 845 (THINGS) and will close in December of this year. The six neon letters of THINGS, mounted mid-wall inside the entrance to the museum’s Education lobby on the basement level, glow in different colors and recall Bruce Nauman’s neons but lack their edge.1 THINGS blazons the good-humored tenor of Creed’s program at the MCA and readies the viewer for pastiche to come.

Martin Creed, Work No. 845 (THINGS), 2007. Collection of Toby Webster, Glasgow, Scotland. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown's enterprise.

The concept behind Martin Creed Plays Chicago is simple: install a hodgepodge of old and new things, proceeding upwards and outwards, placing works first within the MCA’s building and later in its garden and plaza. Periodically Creed will punctuate this plodding crescendo with a performance, such as February’s lecture entitled “I Like Things;” which, despite its title, failed to clarify his attitude towards things.2 And in the fall, he will engineer a finale of sorts with his first ballet at the MCA’s theater.

Despite the clarity of this program, Creed’s works at the MCA so far neither build upon one another nor remain discrete “things.” Rather each work and installation attempts, with varying degrees of success, to blend in with its surroundings. Disguised as art you have seen before, Creed’s works summarily function as minor meta-commentaries probing the meaning of art and the role of artist. Nevertheless they fail to explore these questions as elegantly as Nauman did, for example, in 1967 with The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths.3 In May, Creed contributed the two most visible and accessible works in Martin Creed Plays Chicago: a pair of large wall paintings, à la Lewitt, decorating the two-story walls of the main lobby. The tart red diamonds of Work No. 1349 (2012) hastily dot the wall left of the lobby’s central axis, creating a lattice of negative space; the hard-edged black diagonal stripes of Work No. 798 (2007) on the right sweep the eye up with force. These wall murals, whose patterns break for air-conditioning vents, electrical sockets, and even wall text, demonstrate the ease of Creed’s formal and conceptual process and highlight his curious relationship with repetition. Bounding from one style to another, Creed eschews reflection on his own past works as well as those of others, leaving behind a string of “things” unified solely by his name and another work number. This aggregate grows year by year, insipidly mocking metaphysics and forgoing thoughtful engagement with material for the sake of prolificacy.

Martin Creed, Work No. 798 (2007) and Work No. 1349 (2012), 2012. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown's enterprise, New York. Installation view, Martin Creed Plays Chicago, MCA Chicago, 2012. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

Creed’s three-foot tall Lego tower, Work No. 792 (2007), playfully mingles with its surroundings on the fourth floor. Legos, stacked singly, stand on a large white platform in front of a long blue wall which prominently announces the exhibition Skyscraper: Art and Architecture Against Gravity. From most angles, this mini-monument, installed in June to coincide with the opening of Skyscraper, might as well be a part of that show. From another angle, the tower, cordoned off by a negligible stanchion, could be confused—and was—as part of “Build Your Own Skyline,” the interactive space where children can adhere primary-colored geometric gels to the museum’s windows. As I watched a child swipe for the Legos, I heard myself shrieking, “You can’t touch that! It only looks like a toy.” As soon as the words escaped my mouth I realized the cheap foundations of my hasty defense. I was thinking about insurance values rather than mystic truths. Perhaps this is how Creed intends to play Chicago: making cynics out of believers and kids out of kids.

Other works fit less agreeably in the MCA’s notably difficult spaces. Work No. 405: Ships Coming In (2005) and Work No. 1355 (2012), installed in February and May respectively, are tucked into a narrow space on the second floor between an elevator bank and a balcony that looks out onto the lobby. Angled awkwardly in the far corner against the railing are the two stacked TV monitors of Ships Coming In. Each screen features a looped video of a boat docking at a harbor shot from the same perspective. While the ship and harbor featured in each video are identical, the manner in which the ship docks, the pedestrian activity on the harbor and the slight atmospheric changes in sky task the viewer to play a game familiar to anyone who spent time as a child with Highlights magazine: Spot the Differences. Sitting in a black leather chair some fifteen feet away from the monitors, I was more amused by my new appointment in a Maxell ad than I was blown away by the nostalgic pleasure of registering banal differences between scenes. Even still, this is the most captivating work in the show.

Martin Creed, Work No. 792, 2007. Collection of Honus Tandijono. Installation view, Martin Creed Plays Chicago, MCA Chicago, 2012. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

To the left of this setup, on the wall between the elevator door and what might be a door to an electrical closet, are twelve evenly spaced nails hammered in the wall diminishing rhythmically in size and degree of protrusion from left to right. Work No. 1355 (2012) was presumably created for the MCA, but its placement near an elevator that ascends and descends does little to enhance its conceptual appeal. The feeble joke is easily understood and, worse, short-lived. Too often parodying “classic” works from the 60s and 70s, Creed’s works amount to a tuneless cacophony.

What the works in Martin Creed Plays Chicago lack in rigor, they make up for with the droll unpredictability that defines Creed’s chameleon-like oeuvre. His mounting number of works promise never to repeat themselves, and the ongoing installation at the MCA ensures at least a good treasure hunt and hopefully some healthy reflection on what makes art good.

- 1. Equally as pithy and informative is the permanent painted sign hovering above the education information desk opposite THINGS: “Hi!”

- 2. He repeated “I like things” over a dozen times and finished the lecture with two stanzas of “No.”

- 3. Nauman has been working in various media since the mid-1960s, and his neon sculptures form a notable but relatively small portion of his overall body of work. Most often these works engage in word play, with colored tubes flashing on and off in cycles in order to form series of anagrams, often with contradictory meanings. These pulsing lights entrance the viewer and, for all their acerbity and bawdiness, function as pragmatic ironies. Likewise, The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths incites contemplation of those tangled relationships between meaning, truth, and aesthetics.