from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

There is no archive in which nothing gets lost

Walking into the cavernous expanse of the Glassel School of Art's main atrium, it would be easy to miss the three video works—by Sonia Boyce & Ain Bailey, Lorna Simpson and Wangechi Mutu—that comprise Sally Frater's first show for her curatorial fellowship in the CORE Program. One work is ensconced in a small room, and another is around a corner in a narrow corridor. The largest video, by Simpson, is the only one clearly visible in the public space of the building. The title appears writ large on the wall by the entrance; its double negative immediately glaring. It suggests the impossibility of an archive where nothing is lost; that is, it makes clear that all archives lose something. It deploys two negations in place of a more "natural" statement of fact, evincing a willingness to play with syntax and with the usual order of things.

The title of the exhibit does a lot of the work for the show, especially as it highlights the fact that all the videos draw from archival or (falsified) historical footage. Sally Frater emphasized in an interview on Glasstire that the three works are distinct and should not be conflated. Of course, the dangers of glossing over difference are real, especially when writing about the work of four contemporary artists, all of whom are women of "African" descent (in quotes since "Africa" is hardly unitary itself). And yet, I think there is something to be learned by reading their three interventions together. These three works together raise compelling questions about archival loss and narrative re-creation.

Lorna Simpson, Corridor (Day), 2003; video still from Corridor; courtesy of the artist.

As I thought about the archive and those left out of its embrace, I was reminded of the work of literary scholar Saidiya Hartman who has written about the archive as "death sentence," referring to the way that it relegates certain lives, particularly the lives of enslaved African people, to the tiniest of footnotes (and usually to mark a particular moment of trauma or disgrace). Because of this fact, she writes that “it is doubtless impossible to ever grasp [these lives] again in themselves, as they might have been ‘in a free state.'"1As Hartman herself and the artists in the exhibit attest, there is a continual, failed attempt to re-create an archive of all that is missing.

In Corridor, a double video projection by Lorna Simpson, I'm left thinking about all that is hidden in these calm and careful depictions of the lives of black women separated by a hundred years: from 1861 and 1961. On the left is an actor (Wangechi Mutu) costumed in a kind of period film, slow, languid shots, excessively pristine, writing letters late at night, walking around slowly in a domestic space. On the other side is the same woman in 1961. There is no violence in either picture, no Civil War or Civil Rights Movement, no suffering or deprivation, no readily apparent critique. It would be easy to walk right by, seeing the 1861 image as a quaint historical reenactment and the 1961 scenes as a pastel mod fantasyland. And yet the absence of these symbols reminds a critical viewer of all that is elided in dominant portrayals of history, i.e. those documents that reach the archive. The videos point to what does not exist within the archive: the textures of black women's lives. The videos highlight absence as a way of critiquing that which is visible.

Wangechi Mutu, Cutting, 2004; DVD, single channel, 5 min. 45 sec., loop; courtesy of Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Each of these artworks as well as the exhibit’s curation embodies a tactic of narrative restraint, a reluctance to tell a linear story or to elucidate all aspects of a particular history. This narrative restraint appears perhaps most clearly in Wangechi Mutu’s video Cutting, in which the artist enters the frame and proceeds to rhythmically hack away at a log in an expansive desert landscape before finally laying down her machete and leaving the frame. The MFAH’s press release for the show divulges the video’s location, yet I found this explanation to be a bit unnecessary. The questions raised by the lack of a particular location are rich enough. The image’s placelessness forces the viewer to scan through a wide array of possible locations, opening up myriad meanings and foregrounding this refusal to fill in the gaps, the refusal to lay out easy answers.

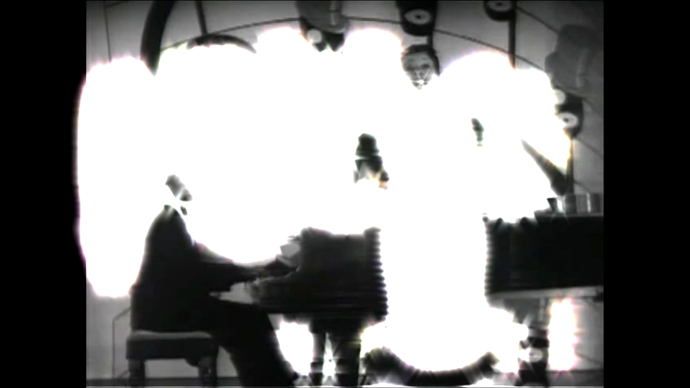

Sonia Boyce's Oh Adelaide in collaboration with sound artist Ain Bailey, pushes even further towards Hartman’s second dictum: "an imperative to respect black noise—the shrieks, the moans, the nonsense, and the opacity." Rather than filling in all the blanks, the gaps themselves become visible both visually and aurally. In this film, Boyce re-purposed archival footage of singer Adelaide Hall and combined it with a soundscape made by Bailey using an audio recording of Hall's wordless vocals from the song ”Creole Love Call." Feedback and sonic detritus litter the soundtrack; the noises sound loudly and unpredictably, catching the observer off guard. The noises seem oddly human, yet manipulated and fractured by digitalization. A patch of white burn-out further obscures the video, blocking most views of Hall's body or face. The visuals and audio are an investigation into noise and opacity, interestingly framed within a "Devotional Series" that attempts to memorialize Black British female singers. Again, we are faced with the question of memory and forgetting, this question of how an archive or a counter-archive functions and fails simultaneously.

Sonia Boyce in collaboration with Ain Bailey, Oh Adelaide, 2010; single screen video with sound,7 min, 12 sec.; courtesy of the artist.

This small, yet powerful exhibit gathers together three video works that—when read together—suggest the extent of what has been lost in the archive, yet refuse to fill in the gaps. Rather, each provides complicated evidence of what is missing, what is not visible, reminding the attentive viewer to investigate beneath a dominant history that is hardly singular.

- 1. Hartman, Saidiya."Venus in Two Acts." Small Axe 2008 Volume 12, Number 2: 1-14