from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

Illusions of Grandeur

The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries, with vast air shafts between, surrounded by very low railings…1

Inside Outer Space Confliction

* * *

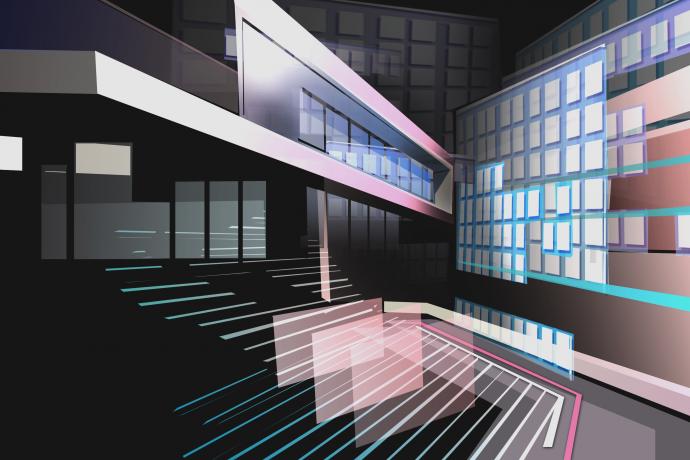

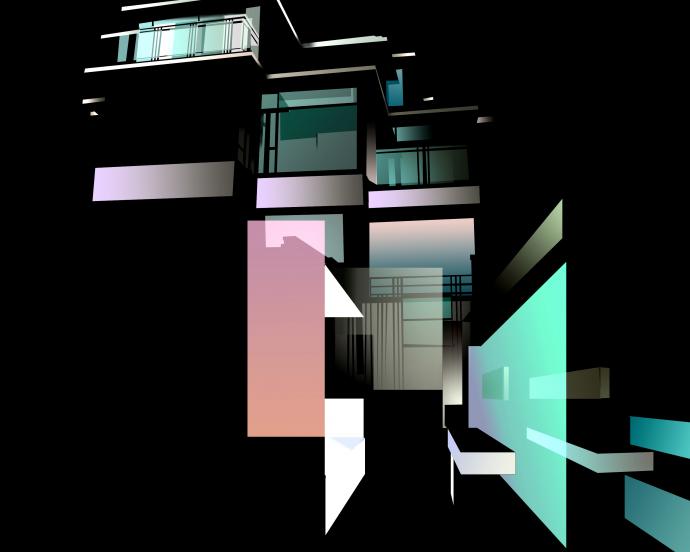

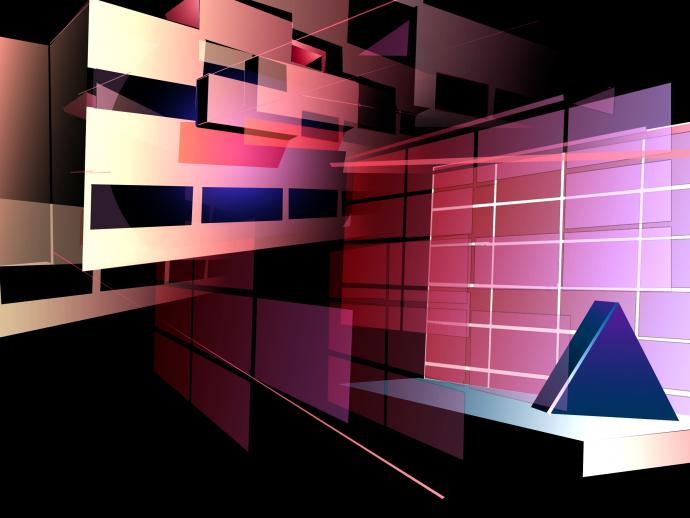

Leah Haney, A Modernist Exterior is Quite-All-White/ Cold Lobby… Is that strollers in the corner?, 2011; Photoshop rendering; courtesy of the artist.

* * *

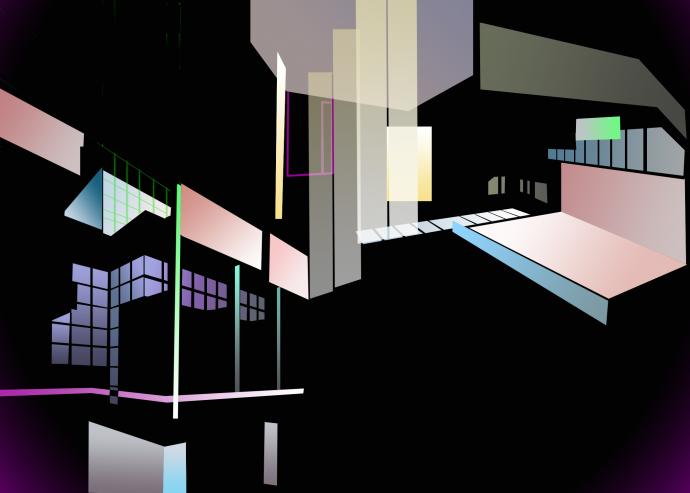

Leah Haney, The Wooden Dwelling Converges/ Viscera of Modern India, 2011; Photoshop rendering; courtesy of the artist.

* * *

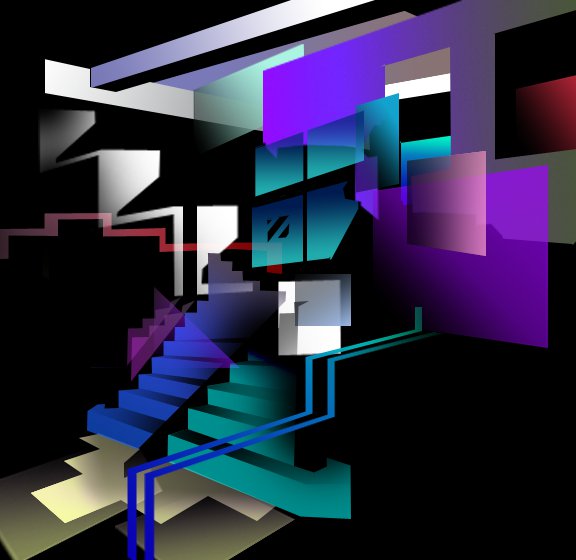

Leah Haney, Industrial Sky Ridge/ Vanishing Deco Stairway Reflected, 2011; Photoshop rendering; courtesy of the artist.

* * *

Leah Haney, This Jutting Glass Domicile/ Inside a No-fuss Quadrangular Habitat, 2011; Photoshop rendering; courtesy of the artist.

* * *

…one of the penalties paid for literacy and a high visual culture is a strong tendency to encounter all things through a rigorous storyline, as it were. Paradoxically, connected spaces and situations exclude participation, whereas discontinuity affords room for involvement. Visual space is connected and creates detachment or non-involvement. It also tends to exclude the participation of the other senses.2

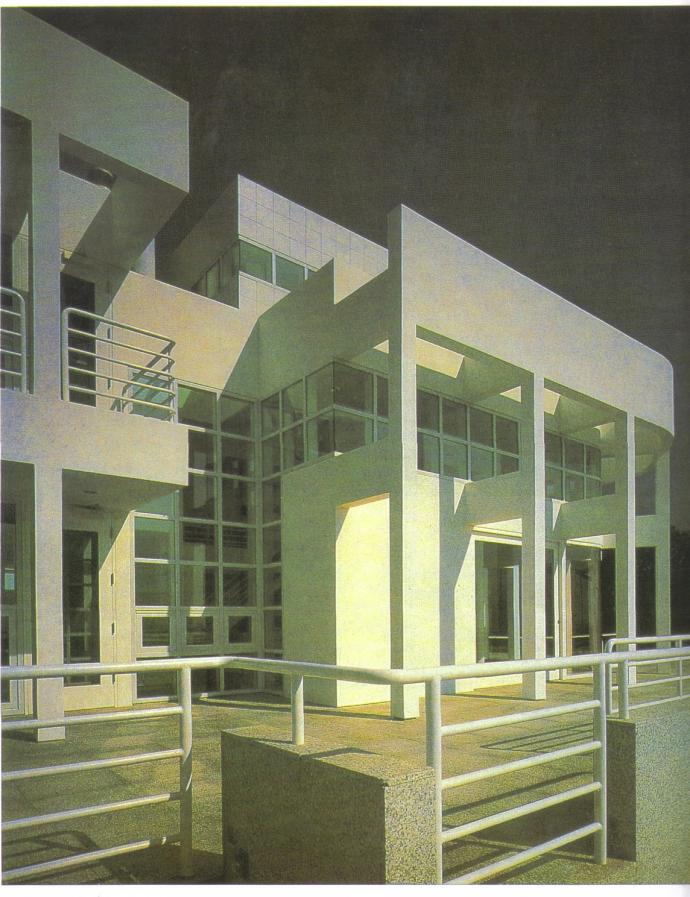

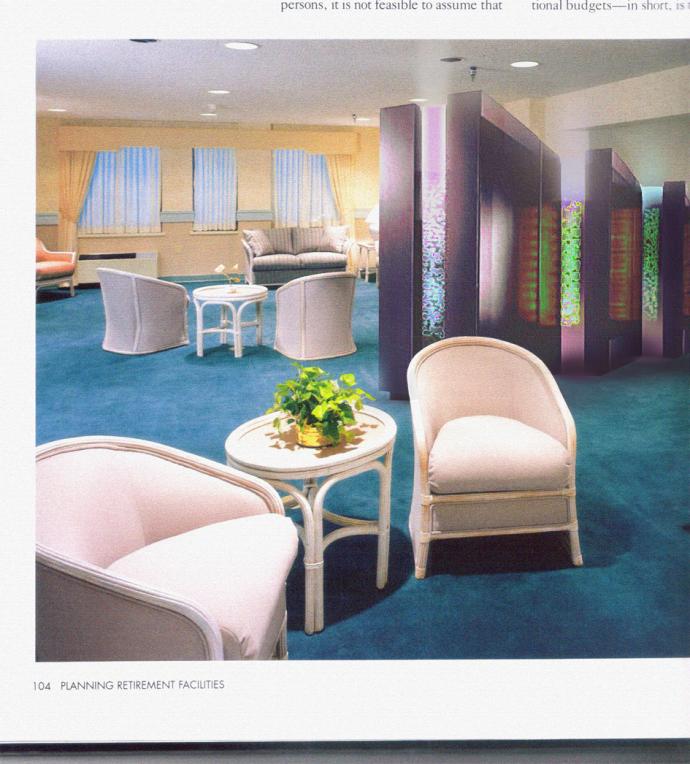

Leah Haney, Scanned Image from Architecture Book, 2011.

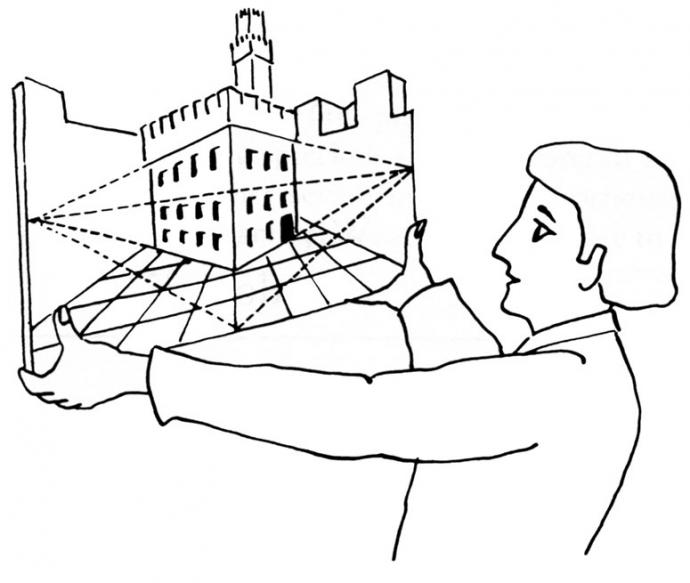

Artist and architects have experimented with depicting space on a two-dimensional surface for hundreds of years. From Brunelleschi to Mies van der Rohe, architectural rendering tradition gives several ways of representing three-dimensional space: floor plans, isomorphic drawings and renderings of what-the-space-will-look-like in linear perspective.

Exterior renderings appeal to a collective viewpoint. Architects imagine and create with the intention that the building will be viewed by many, and affect space by intrusion. The buildings impose on space in a way not unlike a statue or an object. Edifice implies the impersonal. The personal body has no influence on the structure in space except to imply scale, as seen in the collage renderings of Mies van der Rohe.

Left: Interpretation of Brunelleschi's first painting in linear perspective; via The Arrow in the Eye. Right: Argitect, Collage with Frank Stella's Delphine and Hippolyte (1967) inserted in Mies van der Rohe's Museum for a Small City (1937); via The Lying Truth.

Exterior architectural renderings accentuate a grander space where the structure is a tool for defining outer space, but images of interiors align with our lived space. Walls and ceilings are protectors—they enclose the body and evoke thoughts of home and ownership. Images of interiors are connected to a personal spatial sensibility.

We comfort ourselves by reliving memories of protection. Something closed must retain our memories, while leaving them their original value as images. Memories of the outside world will never have the same tonality as those of home ... 3

In a society characterized by ever-increasing individualism and isolation, interior space—in its details and limitations—is relatable and easily understood even in the simplest renderings. Particularly in an age dominated by computers and the Internet, people live on two-dimensional computer screens surrounded by a myriad of not-necessarily-connected images. Even the experience of exteriors becomes a viewing in an interior (the computer screen). Perhaps it’s not so different than old architectural renderings on paper, but I believe that the relationship to the computer changes how people respond to and appreciate images of three-dimensional environments.

Both images: Leah Haney, Untitled (Altered Scans from Design Books), 2011; courtesy the artist.

A lot of my prophecies about the alienated society are going to come true ... Everybody's going to be starring in their own porno films as extensions of the Polaroid camera. Electronic aids, particularly domestic computers, will help the inner migration, the opting out of reality. Reality is no longer going to be the stuff out there, but the stuff inside your head. It's going to be commercial and nasty at the same time, like "Rite of Spring" in Disney's Fantasia ... our internal devils may destroy and renew us through the technological overload we've invoked.4

About a year ago a sculpture project I was working on led me on a wild-goose chase in search of old architecture models. I called firm after firm to no avail. All had made their models over the last ten years digitally. The only physically available models existed in the University’s architecture department, which budding architecture students had made.

Digital rendering picked up in the early nineties, and has vastly evolved. The computer screen is where a building is now born. These computer renderings bridge digital fantasies and the real world, and only prove the immense impact the computer has on space.

Left: Odile Decq and Benoit Cornette. l'Arca 94 June 1995: cover. Right: Loris G. Macci. l'Arca 84 July/Aug 1994: 27. Both via RNDRD.

The computer is a portal to infinite resources. The Internet bombards us with images and information. More often than not viewers experience these things in isolation. The person-to-computer relationship is an intimate one. Images and their significance are revaluated when viewed on a computer screen. Viewers can abandon an image with the click of a mouse after only viewing it for a matter of seconds. Images rely on the viewer’s whims.

So how does the screen affect perception of space? Renderings of space remain rooted in illusion; since Brunelleschi, architectural rendering depends on making something flat seem three-dimensional. Now instead of approaching an image of space in a book or on paper the image sits glowing on the computer alongside the Internet’s infinitude. The Internet is intangible: its information and images are an illusion. Anything viewed on the computer screen encourages a certain amount of doubt. This is accepted and ingrained in anyone accustomed to using the Internet.

The Internet balances belief and doubt, reality and fakery, isolation and community. Though illusion is at the heart of rendering two-dimensional space, in fact the computer enables a new understanding of space. It charges space with the same sensibilities and fantasies seen everyday on the computer, themselves always imbued with potential unreality. The Internet empowers the idea of illusion but not without a dash of skepticism.

Nothing falls prey to skepticism more than computer-generated images; specifically Photoshopped images. On billboards and advertisements along the sides of buses and in every magazine today are examples of butchered Photoshop images. The website www.psdisaters.com is a blog that catalogues the worst Photoshop mistakes found in print and on the web. With culture’s computer-trained eye, Photoshop fools few these days.

When playing around with Photoshop one experiment I undertook involved Photoshopping colorful sci-fi-like objects into images of retirement homes. For hours I tried to integrate a giant supercomputer into a photo of a pale-pastel lounge that I had scanned from a retirement home design book. But, no matter how much I tried to disguise and adjust the images, it never totally blended. I dropped shadows, used brush tools and gradient presets. I layered and blurred grain filters—transparent and opaque, but it ended up just looking cheesy and … well … Photoshopped.

Another of my lil’ Photoshop projects ended up differently. My parents had emailed me from an Alaskan cruise they’d taken earlier this summer. It said, “We are having a blast … ” and “ …your mother rode a kayak ... Wish you were here!” They attached a photo taken with an iPhone of them waving. I must have had some time on my hands that day, because I took the image and Photoshopped my two sisters, my dog and me into the photo and sent it back to them as if we were all there in that tiny ship cabin. It took minutes. I even tried to make it as obvious as possible for kicks.

Leah Haney, Untitled, 2011; Photoshop rendering; courtesy of the artist.

When comparing the two images, the one that is more “convincing” is the fake family photo. It’s not convincing because it’s believable, but because it isn’t trying to trick. When it comes to computer-altered images, the more obvious the better. It’s a collage. Typical collages not made on the computer aren’t trying to trick either—no illusions. In the sixties, many artists experimented with combining images. They intentionally drew attention to the differences between the images and therein lay the work’s power. This is the opposite of Photoshop’s initial intention, to adjust and combine images flawlessly as if in one photo.

But, Photoshop is not all bad—by exploiting the skepticism against them, Photoshop-created-images become self-aware. The simplest shapes, filters and gradients—once viewed as cheesy and contrived—instantly become a viable reality. The admittance of illusion makes room for belief in an image just as one accepts any image on the Internet or an architectural rendering in space.

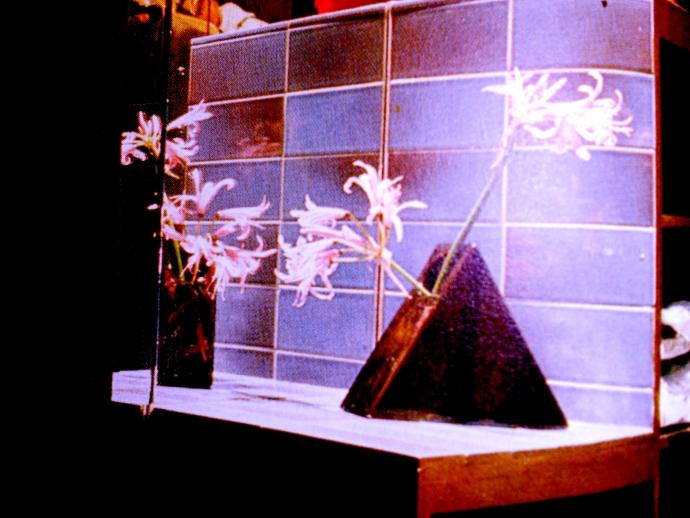

Leah Haney, Not a Parking Garage/ Lost Alien Artifact, or Awesome Vase on a Shelf?, 2011; Photoshop rendering; courtesy of the artist.

- 1. Jorge Luis Borges, The Library of Babel (Boston: David R. Godine, 2000).

- 2. Marshall McLuhan, Through the Vanishing Point: Space in Poetry and Painting (HarperCollins, 1968): 240.

- 3. Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space. trans. Maria Jolas (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994). Originally published as Poétique de l'espace by Orion Press in 1964.

- 4. J.G. Ballard, "Interview in Heavy Metal" (April 1971)