from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

On Archives and Absence

You know perfectly well that despite the infinite heaps of things they recorded, the notes and traces that these people left behind, it is in fact, practically nothing at all. There is the great, brown, slow-moving strandless river of Everything, and then there is its tiny flotsam that has ended up in the record office you are working in. Your craft is to conjure a social system from a nutmeg grater…1

Many of [Aaron Burr’s] personal records went down with the Patriot when Theodosia drowned. So the historical record is incomplete. [Thomas] Jefferson’s writings presently occupy thirty-three modern volumes (in a project that commenced in 1950), and are still being compiled and edited, down to the last detail. [Alexander] Hamilton’s writings are contained in twenty-seven published volumes. Burr’s in two.2

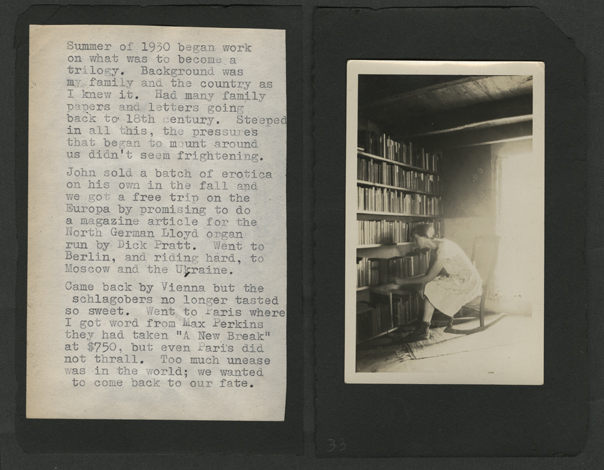

Tucked in the back of a box of the John Herrmann collection at the Harry Ransom Center is a small album of photographs. Glued into the album with care, most of the photographs are accompanied by a page of typed descriptive text. They are almost all images of house interiors. One depicts the sink and kitchen, another shows a woman sitting on a rocking chair and perusing the bookshelf in the living room with sunlight streaming in the window behind her. The homes in the photographs are farmhouses, one in Connecticut and, then later, one in Pennsylvania. Outdoor shots document a garden, a cat—Mrs. Gummidge!—apple trees in bloom, and the occupants of the homes: writers John Herrmann (1900-1959) and Josephine Herbst (1892-1969), who were married from 1926 to 1940, though they separated in 1934. A handful of the images are of Herrmann and Herbst on vacation in Mexico and on a fishing trip near Key West with Ernest Hemingway. Observations about the refurbishing of the Pennsylvania farm house—tearing out a plaster ceiling, replacing windows, removing doors, building cupboards—are interspersed with mentions of Herbst’s publications: the writing of her novels and short stories appears to be part of the work of the home.

Herbst made the album sometime after the couple separated, since all of the text is in the past tense. But despite the intimacy of the album’s subject, in her commentary she never alludes to their breakup, to their arguments, to Herrmann’s alcoholism, or their affairs. Instead, she considers the objects of her home closely, and then she pans outward, to the state of the world in the 1930s, with mentions of the 1932 presidential election, the Spanish Civil War, and her travels to Cuba, Germany, and France. “As the world was falling apart, we shored up the house,” she writes.

The album comes with no explanation of why it is in John Herrmann’s collection or when it was made exactly. Perhaps it was a gift to her ex-husband (though throughout it, she refers to him as John, not as “you”). Perhaps she meant the album as a recollection of their domestic partnership, or perhaps it served as a collection of memories about a specific time in her life—the time when she was publishing and building close friendships with other writers. On a page next to a photograph of her mother and sisters taken in 1920, she types, “Time is also memory.”

Page from the album of Josephine Herbst; c. 1920s - 1935; image courtesy the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

An archive is a collection, has been collected, exists because a person held on to things. (See my difficulty in finding the active voice here; the archive is, has been. Even in my language, I lean toward the archive’s omniscience as if it has always been.) An archive consists of remainders, lucky scraps of paper saved from the dustbin to be filed away in acid-free folders and (sometimes) systematically labeled. An archive also consists of absences, of missing pieces and unclear relationships between objects and people. Archives can obscure even as they illuminate.

At the same time, reading an archive changes one’s constitution, the way one understands all the texts—and all the objects—that have come before and all that will come after. In his novella The Literary Conference, Argentine writer and critic César Aira touches on the archival capacity of the human mind: “… every mind is shaped by its own experiences and memories and knowledge, and what makes it unique is the grand total and extremely personal nature of the collection of all the data that have made it what it is. Each person possesses a mind with powers that are, whether great or small, always unique, powers that belong to them and to them alone.”3 The encounter, then, between the researcher and the archive is akin to magic. Its happening is always necessarily a unique instance of different bodies of knowledge coming together.

When I tell someone about my research, my stories often follow a certain narrative arc. I travel alone to a place (often rather remote), I look through piles of things and papers and photographs, I find one (or two or three) particular things, papers, and/or photographs that no other historian has studied closely or written about, and I come away feeling overwhelmed by data, hopeful that one thing will make it into my project. “I found the missing piece!” I’ve heard scholars proclaim as they step away from a reading room to smoke or make a phone call or drink coffee. There is something compelling about archival research, something that allows one to think she will discover an answer, or see something old with new eyes.

There are, also, the related side stories from my trips. These stories form a backdrop for my research; the characters I met while driving through rural Alabama, the uncomfortable places I stayed while researching in South Carolina and Louisiana, the warm welcome I received from the regulars at a bar in Tuscaloosa, the advice—so much advice!—I received from people I met on the road. These are the stories I tell to indicate my presence in a place, to suggest, perhaps, a kind of authority through familiarity. Cultural historian Carolyn Steedman writes of this presence as it is symbolized by footnotes in a text:

The historian’s massive authority as a writer derives from two factors: the ways archives are, and the conventional rhetoric of history writing, which always asserts (through the footnotes, through the casual reference to PT S2/1/1) that you know because you have been there. … [Authority] comes from having been there (the train to the distant city, the call number, the bundle opened, the dust), so that then, and only then, you can present yourself as moved and dictated to by those sources, telling a story the way it has to be told.4

I’m not sure how Josephine Herbst’s story needs to be told, nor have I visited the place where she lived. Her friend Hilton Kramer, entrusted with her papers after her death, describes her as “a peculiarly significant failure … a failed writer and … a failed woman.”5 Her strong attachments to men and women often drove them away, he writes, leaving her miserable and alone to write mediocre novels in her farmhouse. Her album of descriptions of that home, however, indicates less misery than devoted attention. For Herbst, the farmhouse seems to have been a center for her most cherished memories, and the place where she spent most of her time. The breakups, the difficulties of writing, are not immediately apparent in the album; instead, it is oblique and resists deciphering. A photograph of Marion Greenwood, with whom Herbst fell in love, is marked only “Marion Greenwood doing frescos for a hotel in Tasco.” In the photograph, Greenwood gestures grandly, holding her brush to the wall and looking over her shoulder toward the camera while Herbst sits at her feet like an attentive disciple. “It’s hard to know what to do with texts that resist our advances,” writes literary and queer studies scholar Heather Love.6 It’s hard to know what to do with absence and with misplaced things. Herbst’s album is interesting precisely because of what it leaves out and precisely because it has also been left out: tucked in the back of John Herrmann’s collection, thousands of miles from the bulk of her papers, the album is something of a mysterious foundling.

What Herbst’s album suggests to me is the incompleteness of all historical records and the ways in which they are always in the process of being remade. In her biography of Aaron Burr, Nancy Isenberg fights against a historical narrative she finds profoundly biased against her subject. The negative bias, she writes, is compounded by the destruction of most of Burr’s archive, which was lost at sea with his daughter. She contrasts this absence to the impressive number of papers that remain from Thomas Jefferson’s archives, and yet, despite their quantity, Jefferson’s writings also contain shattering absences. What Herbst’s album suggests is that absences in the archive can be made productive, can be confronted, can counter accusations of failure, or can make failure something infinitely more complicated and interesting than success. Absences in the archive remind us of our own role in knitting together the “tiny flotsam” we find gathered there. How to make those pieces speak to a way of being in the world—how to marshal them into a narrative that might have consequences in the present—is what is at stake when we face their incompleteness.

This article is part of " At the Weehawken Dueling Ground, July 11, 1804,” by Andrew Douglas Underwood. Other parts of this project include:

At the Weehawken Dueling Ground, July 11, 1804 by Andrew Douglas Underwood

The Duel - Source Archive by Andrew Douglas Underwood

The Duel: An Interview with Andrew Douglas Underwood

Burr by Michael Agresta

and our editor’s statement

- 1. Carolyn Steedman, “Something She Called a Fever: Michelet, Derrida, and Dust,” The American Historical Review 106, no. 4 (October 2001): 1165.

- 2. Nancy Isenberg, Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr (New York: Viking Penguin, 2007): 405-406.

- 3. César Aira, The Literary Conference, 2006, trans. Katherine Silver (New York: New Directions Books, 2010).

- 4. Steedman, 1176.

- 5. Hilton Kramer, “Who Was Josephine Herbst?” The New Criterion 3 (September 1984): 1. The bulk of Herbst’s papers are now housed at Yale’s Beinecke Library in 134 boxes; this small album is just a tiny fraction of the archive she produced, and it has been separated from most of that archive.

- 6. Heather Love, Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007): 8.